EV fire risk is already here.

Lithium-ion batteries are now part of daily life, and building surveyors across Australia are confronting a growing question: will our buildings perform when batteries fail?

The growth in electric vehicles (EV) sales in Australia and overseas is the start of a long term trend away from Internal Combustion Engines (ICE).

The use of lithium ion batteries in vehicles, battery storage systems and smaller applications such as scooters, bikes and personal appliances has resulted in a new set of fire risks that are different from anything we have seen in the past, presenting multiple issues for building surveyors and other fire safety practitioners.

While future technologies like solid-state batteries or hydrogen fuel cells may reduce these risks, lithium-ion batteries are the standard for now. And all indicators suggest they’ll remain dominant for at least the next decade.

This article explores how these emerging risks align (or fail to align) with current regulatory frameworks, particularly the Building Code of Australia (BCA) volume 1 in NCC 2022. It aims to provide clarity around what is required, what is emerging, and what lies in the grey areas of professional judgment.

Let’s get into it.

A Different Kind of Challenge

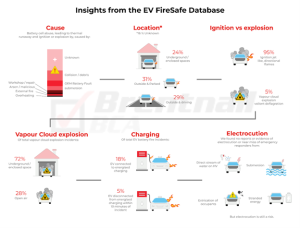

Current evidence suggests that EV fires are far less prevalent than ICE fires (Fire & Rescue NSW Report D25/20316, March 2025), with ICE vehicle fires occurring around 5-7 times more often than EV fires in NSW.

It is unclear if this will change as batteries age or battery compositions and production techniques are modified.

The overall likelihood of EV fires remains lower than that of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles but EV battery fires have the potential to become significantly more widespread as worldwide production ramps up.

➡️Intense and Prolonged Fires

EV battery fires can be extremely intense and difficult to extinguish. They can reignite repeatedly, even after appearing to be extinguished, requiring specialised firefighting techniques, prolonged suppression efforts and significantly more water.

➡️Toxic Smoke and contaminated fire water

- The chemical compounds in lithium-ion batteries release toxic fumes and contaminate fire water, posing significant health risks to firefighters, building occupants and the surrounding environment.

➡️Rapid Spread

Battery fires generate intense radiant heat that is often projected sideways from the base of the car, allowing fire to quickly spread to adjacent cars or nearby building fabric.

The pace of fire growth and spread from lithium ion battery fires has affected brigade operations. Where previously they may have arrived during the development phase of a vehicle fire, the rapid growth now means that the fire is often fully developed before they arrive.

➡️ Vehicle weight

EVs are generally heavier than their ICE counterparts due to the weight of battery packs. Similarly, ICE vehicles are also getting heavier, to the point where some vehicles exceed the design capacity of carpark building structures..

Combined with a structure weakened by fire, this additional vehicle mass has the potential to cause a failure of carpark structures.

Current Position of The BCC And NCC on Ev Fire Safety

Each requirement of Building Code of Australia (BCA) is created in response to new ways that buildings are used, new construction materials and techniques, or changes in the standard that communities expect from buildings.

BCA requirements reflect the minimum agreed standard accepted by the whole community. There will always be some that believe the rules should go further and others that believe that the rules don’t go far enough.

There are processes in place to prevent over-reactions to changing circumstances, balancing public safety against cost and complexity.

For changes to be made to the BCA, there needs to be an accepted body of evidence supporting the introduction of new requirements before a change is accepted for the code.

EV fire data in Australia generally indicates that EV fires are far less prevalent than ICE vehicle fires, but that their effects are far more significant when those fires do occur.

Whilst there is some anecdotal evidence and a growing body of research quantifying the additional risks for Lithium-ion battery fires, there is not yet sufficient evidence for the Australian Building Codes Board or Standards Australia to make changes of any significance.

The current risks are not so significant that the ABCB needs to make changes to the BCA, but with a rapid uptake of EVs, those risks will definitely increase over the life of buildings that are being approved right now.

The current BCA, in NCC 2022, does not contain any specific additional provisions relating to EV fire safety. While EV charging regulations are still developing, there are no clear requirements that address how these systems should be managed in the built environment.

When NCC 2025 comes into force it will likely include some minor additional fire safety requirements. They are likely to include:

- Requiring sprinkler protection in all carparks with more than 40 cars, irrespective of whether they meet the NCC definition of being an ‘open-deck’ carpark or not.

- Requiring sprinkler protection to car stackers located within carparks.

- Removing some Fire Resistance Level (FRL) concessions for open-deck carparks and sprinkler protected carparks.

In time, as the body of evidence increases, there may be additional requirements included in the BCA. There is unlikely to be any further update until NCC 2028, by which time we will have a clearer picture of the appropriate requirements.

There is also the chance that the risks are reduced with changes to battery designs, materials or installation. Laws recently introduced in China, the world’s largest manufacturer of batteries and EVs, require manufacturers to prevent fire and explosion in EV batteries. We will also likely pass this through to other battery types.

Maybe the long term risk isn’t that significant after all.

Long term, maybe not, but there will still be millions of EVs on the road over the next 15-20 years that do not meet this standard, so the risk will be with us for a very long time to come.

When the Rules Aren’t Clear

There are no rules then?

Not quite.

There is justification for applying the current deemed-to-satisfy (DTS) provisions that do not appear to have any requirements because there aren’t any applicable DTS clauses.

The current BCA is structured to allow for changes in the way a building is used, by including clauses that allow us to assess the requirements for special hazards if we believe that they exist. The recent Fire & Rescue NSW position statement on electric vehicles, advocated using BCA Clauses E1D17 and E2D21 for special hazards – these are existing DTS requirements for special hazards.

How these existing requirements are applied depends on the situation and the risk appetite of the building surveyor carrying out the assessment.

Until there is an industry-wide accepted practice or legal precedent on how to apply the current rules, there will always be an area of grey.

As practicing building surveyors our role is to apply the rules as they currently stand and use our expertise in these matters to determine when they should be applied. We also need to provide our clients with enough information for them to make an informed decision on their risks.

When it comes to the grey areas (DTS v Special Hazards v Performance Requirements), that is a matter for individual professional judgement based on the risks associated with the building that is in front of you at the time.

When there’s no explicit clause, achieving and demonstrating fire safety compliance relies on sound professional judgement and your ability to justify the decisions you’ve made.

If you are unsure, research and improve your knowledge so you can justify your decision – then document your reasoning for that decision – someday you may need to defend it.

You should also use your network of colleagues to develop your views. There is no standard industry practice on these matters for now, so the best process you can use to arrive at an appropriate decision is to test your decision with colleagues whose professional judgement you trust.

How Do We Approach The Risk In Existing Buildings?

Existing buildings are always difficult. As they age and the BCA gets updated to include new or enhanced requirements, buildings get further from compliance and closer to the point where it is appropriate to upgrade the building. Whilst there are some legislative triggers to consider if an upgrade is appropriate, there are no set rules for exactly what needs to be upgraded and when, with the exception of accessibility under the Premises Standards.

It is always a judgement call based on the condition and use of the building, the expertise of the building surveyors involved, the needs of the building owner and the views of the fire brigade and local authorities.

We can confidently say though, that virtually all existing building stock has been designed with no thought to the risks of EV fires.

How do we review those buildings?

How do we advise our clients of their best approach?

This is where we need a deep understanding of the risks of an EV fire, the potential consequences to the building occupants, building fabric and surrounding environment and how changes to the building structure, fire resistance and fire services might mitigate those risks.

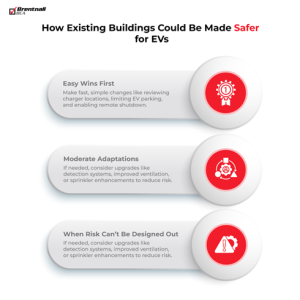

Mitigation Steps for Existing Buildings

Firstly, we need to look for the easy wins – fast, simple and cost-effective ways to improve the risk profile of existing EV charging infrastructure without significant upgrade work. We could look at the locations of EV charging systems, introduce parking restrictions in areas where the building structure is not adequate, adapt charging infrastructure to allow for remote shutdown by fire brigade personnel or provide an onsite emergency services information package.

Charging infrastructure itself needs to comply with AS/NZS 3000 Electrical Installations (Wiring Rules) to ensure standards are met. If there is a need, we might consider some building adaptations that would significantly improve the risk profile of the building without requiring significant redevelopment work. We might consider additional detection systems for an earlier warning or enhanced ventilation or sprinkler systems. Fire modelling might be an appropriate way of quantifying the specific risks.

If the risk is significant and the building unable to be adapted, we need to consider how the use of the building might remain viable until it can be redeveloped. This can be really challenging and requires the building owner to fully understand the risks – we need to know the risks ourselves to provide that advice.

Things That Keep You Off the Wrong Side of Risk

➡️Follow the research and guidance from professional organisations on this topic.

Refer to up-to-date materials from sources like EV FireSafe, Fire & Rescue NSW, AFAC, the Australian Institute of Building Surveyors (AIBS) and the Association of Australian Certifiers (AAC).

➡️Discuss potential issues with your colleagues.

Use peer consultation to test your risk assessments and interpretations of the BCA, especially in cases where there’s no direct DTS clause or accepted practice. Getting a second or third perspective can flag oversights and strengthen your rationale.

➡️Don’t be an outlier

There is no future in being a maverick on this issue. Stick to recognised practice where possible and document your reasoning when you can’t.

Guidance From Other Interested Parties

As the body of evidence develops, there will be no shortage of advice from interested bodies. Currently, position statements have been produced by the following organisations:

- The Australian and New Zealand Council for fire and emergency services (AFAC)

https://www.afac.com.au/resources/4e128301-9ed6-4332-aafe-dc93c4855369 - Fire & Rescue NSW https://www.fire.nsw.gov.au/page.php?id=9447&position=8

https://www.fire.nsw.gov.au/gallery/resources/SARET/Fire%20Safety%20Position%20Paper%20-%20Electric%20vehicles%20(EV)%20and%20EV%20charging%20equipment%20in%20the%20built%20environment%20v1.0.pdf - South Australian Metropolitan Fire Service https://www.mfs.sa.gov.au/community-safety/building-and-commercial-fire-safety/guidelines-and-information

- Australian Institute of Building Surveyors https://aibs.com.au/Public/Public/AIBS_Policies.aspx